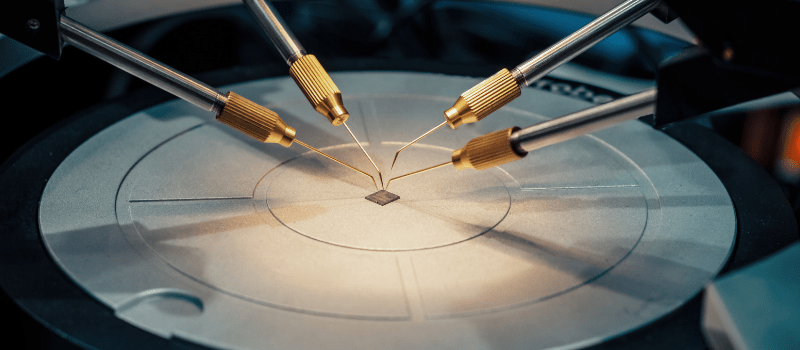

Picking out the appropriate sensor to measure a laser beam (most sensors will measure other types of broadband light as well) has always been quite a challenging issue. We’d like to help you get to know a few of the main criteria to consider when choosing a sensor:

- Your measurement needs – Do you want to measure average power or pulse energy? If power, then choose a thermal or photodiode sensor. If energy, then if the repetition rate is less than one pulse every 5s, you can use either a thermal or pyroelectric sensor. If faster than that, then a pyroelectric.

- Dynamic range – Choose a sensor that will be able to measure the highest and lowest power/energy you want to measure.

- Wavelength region – Make sure that the sensor covers the wavelength region you want to measure.

- Damage threshold – In order to select a sensor that will not be damaged you have to accurately know how much power or energy density you have (not just the total power or energy). Know the beam spot size, and what the energy distribution is (since for example a Gaussian beam has much higher density in the peak of the beam than a flat top or other modal beam). If the laser is pulsed, one also has to know the pulse length in time, as most sensors have a different damage threshold value based on peak power (lower damage threshold for shorter pulses). If you can’t seem to find a sensor that will not be damaged, you can always look into attenuation options including beam splitters, diffusers, ND filters and possibly measuring just the leakage through a mirror.

A few things to pay attention to:

- With each attenuation option the uncertainty of the measurement increases – You may find that it may be better to have 2 sensors, one more sensitive and one able to measure higher power or energy.

- (In case you own a few lasers) Measuring as many lasers as you can with as few sensors as possible is not always recommended. The same sensor wouldn’t necessarily cover the full dynamic range needed for each of the laser measurements, or it may have to sacrifice accuracy to cover their full range.

- Physical size of the sensors: Most end-users usually want the smallest physical size sensor possible, or maybe a large aperture with large sensing area but small housing. You should know: If it’s high power, there may be an issue in cooling the sensor (either through convection, conduction, forced-air, or water). If attenuators are used, the space they require may be an issue.

And in case all of the above information succeeded in overwhelming you…Our well-known tool on the website, the Sensor Finder, automatically calculates the best sensor for the measurement conditions you input and will help you get a good starting point.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *